COVID Pandemic and Its Impact on ASA Members

A modified version will appear in the summer 2021 issue of Acoustics Today – DOI 10.1121/AT.2021.17.2.02

How Are ASA Students Being Impacted by the Pandemic?

‘Bubble’ took on an entirely new meaning to acousticians this past year. Instead of being thought of for its strong acoustic scattering properties, a bubble now holds universal meaning as the isolating social barrier we must maintain to protect against exposure to the SARS-CoV-2 virus. There is no doubt that we have all had to make adjustments to our world view during this pandemic. However, living in a bubble can be insulating. So, to get a sense of what our Acoustical Society of America (ASA) student community has been experiencing, we surveyed students on the impact of the pandemic in their lives. Unsurprisingly, the pandemic has brought measurable setbacks for students. Even so, many students have found ways to adapt. As acoustical oceanography Ph.D. student Ernst Uzhansky (University of Haifa, Israel) remarked in his survey response, “the strongest crisis is the door for the biggest opportunities.” We hope this article begins a dialogue amongst the entire ASA community on supporting our student population as we navigate the long-term changes catalyzed by the pandemic.

Sixty registered ASA students (of 666), from all Technical Committees and specialty groups, responded to our survey on the personal and academic impact of the pandemic. A majority of respondents were doctoral students (82%), while there were also master’s students (10%), undergraduate students (3%), and postdoctoral researchers (5%). Most respondents identified as lab scientists (65%), though others identified as applied scientists (22%), field scientists (8%), theoreticians (3%), or the question was not applicable (2%). Seventy-three percent of all respondents were studying at U.S. institutions.

To begin to understand the impact of the pandemic, students responded to a question asking if their graduation was or would be delayed, accelerated (none provided this response), or not impacted by the pandemic. Over half the respondents will have to delay graduation due to the pandemic, with 45% experiencing a delay of less than a year, and 7% experiencing a delay of greater than a year. Thirty-eight percent of all respondents reported no delay, while the remaining respondents were unsure what the impact would be.

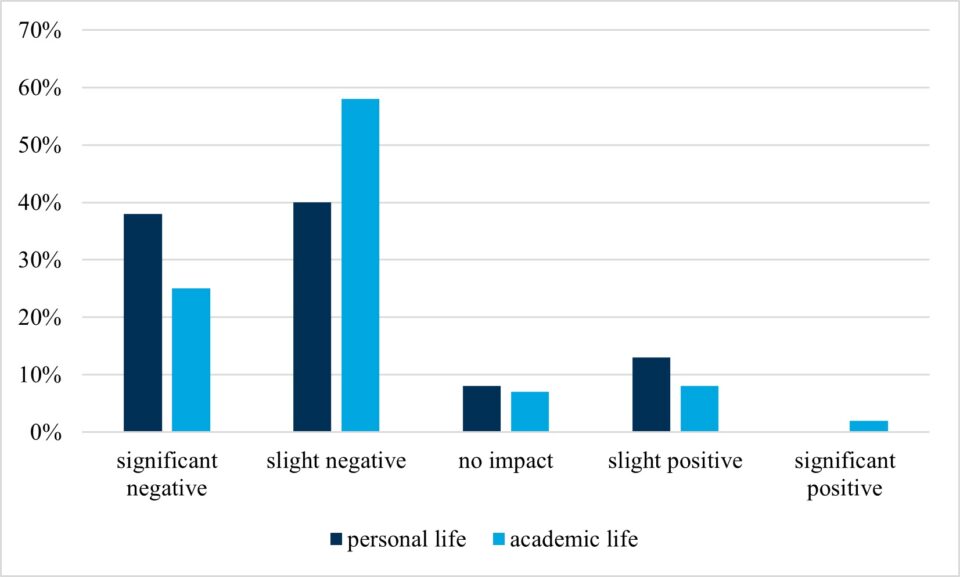

Students were also asked to reflect on the impact of the pandemic in their personal and academic life, rating the impact on a five-point scale. The results are shown in Figure 1 and demonstrate a strong negative trend, with most students rating a “slight negative” or “significant negative” impact of the pandemic on both their personal and academic life. The impact of the pandemic on academic life was more often rated as a “slight negative,” while personal life was split between the two.

|

| Figure 1. Student-rated impact of the pandemic on their personal and academic life (n=60). |

The anecdotes in the following sections bring these answers beyond just numbers, providing insight into specific circumstances, challenges, and personal victories of our students. The ideas presented are either summaries of frequently occurring comments, direct experiences, or quotes from individuals.

The pandemic has impacted the quality and trajectory of student research efforts. New students have had to acclimate to unfamiliar laboratory layouts, as well as interrupted, complex, or hampered protocols. Meanwhile, more senior students had to greatly reduce the pace of experimental data collection to comply with COVID-19 occupancy and travel restrictions, or else stop these activities completely. Consequently, the nature and scope of the scientific inquiry contained within a given master’s or doctoral thesis is under intense reexamination nationwide, according to our survey data.

Some, like Speech Communication Ph.D. student Drew McLaughlin (Washington University in St. Louis, MO), were able to overcome these challenges by moving their data collection online. “Learning to create tasks that operate well online took some learning, but now I’m pleasantly surprised with this approach … [t]he silver lining … is that it allows for larger sample sizes and fast data collection.” Many students have shown great creativity in reworking their schedules to accommodate more writing or computational tasks, while others shifted the focus of their research, like one student who examined the acoustic implications of mask-wearing.

Other career adjustments, however, have not been so positive. Undergraduate students report that their hopes of attending graduate school have become impossible. Some students express frustration that canceled conferences and other scientific events have eliminated crucial networking opportunities and made resumes look conspicuously sparse. Worries of degree delays plague some students who feel that they have been left to struggle through the stress of canceled classes and exams with little to no guidance.

Further, the abrupt transition to researching at home negatively impacted the workday dynamic for many. Isolation from colleagues meant that it was harder for some to focus and feel excited about their research, while others reported that they waited longer before asking for help with new tasks. Practical problems like internet connectivity issues compounded these effects. Most prevalently, students came to miss the intangible elements of working in a group setting: the flow of information and ideas that happens naturally in person felt stilted and artificial online, if it happened at all.

Encouragingly, this experience was not universal, and other students reported that meeting with lab mates, colleagues, and advisors online increased collaborative productivity while still allowing time for the kind of extracurricular topics that maintain vital connections. For other individuals, unstructured interactions with coworkers had made them less productive in an office environment and working with fewer distractions and more flexibility was a refreshing change of pace. In order to strengthen a dwindling social network, the pandemic encouraged some to become more involved with school clubs and professional societies like the ASA.

As the line between work and home has become blurred, the ongoing detrimental impacts on students’ personal lives have the potential to work their way into studies and research. As one respondent wisely commented, “It is all connected.” We are all aware that the effects of the pandemic extend far beyond the reach of our university campuses, research projects, grant applications, and the next meeting with an adviser. The personal cost and consequences of long-term isolation, multiple quarantine periods, and the potential health impacts (mental, emotional, and physical) cannot be overstated.

The majority of respondents expressed that the pandemic has negatively impacted their personal lives, using words like “hopelessness,” “loneliness,” and “extreme isolation.” For those at a higher health risk, the effects of isolation are extreme. Architectural acoustics undergraduate Megan Stonestreet (University of Kansas, Lawrence, KS), shared, “I live alone, and have not seen a single friend in person since COVID protocols came into place, due to being high risk… Living in what I’d consider isolation has ended many, if not most, friendships.” Respondents who had made an academic switch that coincided with the onset of the pandemic seem to be hit particularly hard. Louise Roberts (Cornell University, Ithaca, NY), an animal bioacoustics post-doctorate, shared a concise summary of international students and postdocs who are working through this pandemic, “There are many postdocs that are living abroad, often living alone and in new unfamiliar places. Postdocs are typically in short-term contracts, … so will have had no local support group, but could not return to their home country to loved ones either. The stress of living through a pandemic without being in the same country as close family or friends cannot be overestimated.” The loss of these connections and increasing feelings of isolation do not occur in a vacuum, nor do their effects on students’ work and research.

The silver lining to this global test of our combined personal fortitude seems to be the opportunity our respondents found in increased time with their at-home companions: partners, children, roommates, and pets. One respondent shared, “Pets are life-savers over the pandemic. They offer so much company and emotional support…they keep my life regular.” It is clear that our peers have found support and small pearls of enjoyment during these difficult times with their families (those genetic, found, and adopted). The pandemic has, in some cases, accelerated personal life choices, such as the decision to forgo wedding parties and simply elope.

It appears that the personal cost of this pandemic has been doled out unequally. Many have found small victories and vast support in the everyday interactions with those closest to them; however, for those students separated from loved ones, friends, and family the cost is undeniably high.

So, what can we do? Students who have been able to adapt seemed hopeful about the work yet to be done on their degrees. But not all students had this privilege, and it is evident that a year into this pandemic there are still insufficient systems in place to help them. How do we combat feelings of helplessness in the future? More importantly, what can we do now? And what about the helplessness that falls out of our direct control, such as from government restrictions? These are difficult questions and we do not have the answers, but we hope that we can begin again to talk openly about these issues. Circumstances are different now and it is unrealistic to expect the same modus operandi as in ‘normal’ times.

Overwhelmingly, what we have heard from students is a sense of isolation in personal life and in academic work. If before, checking in on your students and peers at a personal level felt like overstepping bounds, please reconsider this notion. We are all experiencing COVID fatigue and may have become complacent, but it is important more than ever to check in on each other’s mental well-being. We believe this should be part of the ‘new norm’ and encourage you to make it so. Reach out to those around you. Have a virtual lab meeting. Advisors: don’t be afraid to ask your students how they are doing. Have a virtual lunch with friends, or a virtual family dinner with those outside your household. Ensure each person has the opportunity to talk and be heard. For all of us, a good first-step would be to check in on at least one person today. Better yet, make this a regular occurrence.

We were not sure what form this piece would take when we decided to survey students, but it is clear now, that this is an opportunity for us to be aware, adjust, and find ways to offer a sense of community to our fellow students. We look forward to hosting another round of Virtual Student Summer Talks this summer and encourage you to check out our peer-mentorship program, Student Outreach for Networking and Integrating Colleagues (SONIC) (http://bit.ly/3e9Ywkq). We pledge to continue to seek ways to facilitate connectedness, especially in the virtual world, by adapting existing initiatives and creating new ones. Please stay tuned to our social media for updates about other social programming, including the commencement of a virtual coffee break for informally connecting with acoustic peers and colleagues. If you have any suggestions for ways that the Student Council (https://asastudents.org/) can help your student experience in light of the pandemic, or otherwise, we would love to hear from you (asastudentcouncil@gmail.com).

For additional information about the impacts of the pandemic on ASA student members, as well as the impact of the pandemic on other members of the ASA community, please see the article by our colleagues from the Women in Acoustics Committee.

Student Council Social Media:

https://www.facebook.com/ASAStudents

https://twitter.com/ASAStudents

Hilary Kates Varghese |

Kieren H. McCord |

Mallory Morgan |

Elizabeth Reed-Weidner |

Hilary Kates Varghese1,*, Kieren H. McCord2, Mallory Morgan3, Elizabeth Reed-Weidner1,4,**

1Department of Earth Sciences

University of New Hampshire, Durham, NH 03824 USA

*hkatesvarghese@ccom.unh.edu

**eweidner@ccom.unh.edu

2 School of Sustainable Engineering and the Built Environment

Arizona State University, Tempe, AZ 85281 USA

kieren.mccord@asu.edu

3Department of Architectural Acoustics

Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute, Troy, NY 12180 USA

morgam11@rpi.edu

4Department of Geological Sciences, Stockholm University

Stockholm, Sweden