Dave outside his previous home along the St. Johns River, Florida in 2007.

Dr. David M. Green served as President of the Acoustical Society of America (ASA) from 1981-1982. In his tenure as an active member[1] of the Society, Dave was awarded the R. Bruce Lindsay Award (1966) for his role in demonstrating the relationships between detection theory and auditory perception. He was also awarded the Silver Medal in Psychological and Physiological Acoustics in 1990, and the Gold Medal in 1994 for his contributions to theory and methods in audition.

Dave earned a B.A. from the University of Chicago in 1952 and another in psychology from the University of Michigan in 1954. He went on to earn a M.A. (1955) and Ph.D. from the University of Michigan (1958), both in psychology. Dave then went on to work in a professorial role at Massachusetts Institute of Technology (1958-1963), University of Pennsylvania (1963-1966), University of California, San Diego (1966-1973), Harvard University (1973-1985), and the University of Florida (1985-1996). He holds two honorary M.A.s from the University of Cambridge (1973) and Harvard University (1973).

Alongside his career in academia, Dave held a consultancy position with Bolt Beranek and Newman Inc. (1958-1996), which allowed him to apply his expertise to many interesting projects including an analysis of earwitness reports related to the assassination of President John F. Kennedy. He has also served on several influential councils and committees, including the National Research Council and the Committee on Hearing, Bioacoustics and Biomechanics. He was elected to the National Academy of Sciences in 1978.

Dave and his first wife, Clara, enjoyed 25 years of marriage and raising a family of four children–Allan, Phillip, Katherine, and George– before their life together ended to her battle with pancreatic cancer. He later met his second wife, Marian, who was the secretary of the fine arts department at Harvard. In 1996, he and Marian retired to a 17-acre property along the St. Johns River in Florida, where they enjoyed entertaining their four adult children and five grandchildren for many years before completely retiring to Daytona Beach, Florida. Dave and Marian celebrated 40 years of “married bliss” together this past June.

Dave and Marian enjoying retired life in 2008 at their home on the St. John’s River

We had the pleasure of reminiscing with Dave and Marian about Dave’s academic journey and what it was like to be President of ASA forty years ago.

Tell us a little about your career path and journey to where you are now.

I grew up in the small town of Tecumseh, Michigan, which had a population of 2,500.

The high school offered little in the way of science, but I did take two years of math, which I loved.

In 1952, I went to the University of Chicago for a Hutchins’ two-year B.A. That is, upon entering the university all students take 16 exams and for whichever exams are passed, the associated classes are no longer required for the degree. I passed eight exams so I needed only eight classes to complete my B.A. All students took a liberal arts curriculum; lots of great books, by Aristotle, Plato, and Thucydides. Unfortunately, I passed the math exam, so I didn’t get to take any mathematics.

I had planned to join the navy and was interested in flight school. But, the physical exam showed many scars from broken ear drums as a result of multiple middle ear infections. As a result, I failed the physical exam and was told I was not qualified for the navy flight program. I had to think of something else to do. So I enrolled as an undergraduate at the University of Michigan (UM), since it was only 30 miles from where I lived.

I started out majoring in psychology and philosophy, but ended up becoming more interested in experimental work. In my junior year, I started working for Wilson P. (Spike) Tanner in a radar laboratory, the Electronic Defense Group (EDG), within the engineering department. There, I worked along with John A. Swets and Spike on signal detection theory. I enjoyed my time at UM with Spike and John.

In my senior year at UM, I joined a group of eight advanced psychology students and was required to complete a research project, my senior honor’s thesis. I had intended to study how the duration of the signal affected its detectability. We were going to use a visual stimulus, a glow tube modulator. Unfortunately, radar equipment, such as these tubes, were scarce at the end of World War II, so we could not obtain one for my thesis. Someone suggested an auditory signal instead and since all of the other aspects of the project were ready to go, we took this suggestion. We ended up using a pure tone auditory signal and varied its duration. From then on I was interested in hearing more than anything else.

I stayed at UM for my graduate studies in the psychology department and continued half-time at the EDG. Since there were no faculty in the psychology department interested in hearing, I had to piece together mentorships and experiences outside of the department to get the education for which I was interested. I was privileged enough to enlist Gordon Peterson (speech) and Merle Lawrence (medical school), who were both at UM, as well as J.C.R. Licklider at Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT), as part of my thesis committee, along with several psychologists. I was also fortunate in being granted a National Science Foundation pre-doctoral fellowship in my first and third years of graduate studies. In my third year, this allowed me to work with Licklider at MIT. Licklider was another fascinating guy who eventually became an important visionary in the development of the internet (a story for later).

After a short summer visit to Bell Laboratory to complete half of my thesis research, which was on the auditory detection of a noise signal, I returned to Michigan to complete my doctoral studies in 1958. The same year I also started working at Bolt Beranek and Newman (BBN) as a consultant. During my time at BBN I worked on many projects including some with Kenneth Stevens, a former ASA President (1976-1977), on high frequency hearing in adults.

After completing my doctoral degree, I took an assistant professor position in the department of economics at MIT—I was in the psychology section of the department. After five years at MIT, I left for University of Pennsylvania as an associate professor. Some of the highlights during my time there were collaborating with John Swets (who was at BBN) to write our book on signal detection theory, and being appointed as assistant to the chairman of psychology in my final and third year there. I then moved on as a full professor at the University of California, San Diego, followed by Harvard, and finally the University of Florida. There, you could say that I also dabbled in physiology, as I would go to John Middlebrooks’ lab and work with him half a day a week. However, I was always really interested in the mathematical processes, theory, and models of hearing, rather than the physiology.

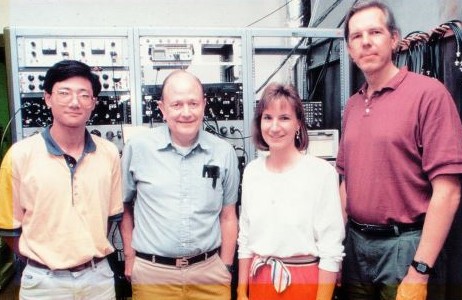

Dave Green with the members of John Middlebrooks’ lab in the 1990s. From left to right: Li Xu (now a professor at Ohio University), Dave Green, Ann Clock (now Ann Eddins, a professor at the University of South Florida), and Dr. John Middlebrooks (now at the University of California, Irvine).

The homestead that Dave and Marian built together along the St. John’s River in Florida. The pond provided the dirt for foundation material, which raised the first-floor of the house by eight feet (shown here is the back of the house). If you look closely to the left of the main house you will see the guest house they also built. It was quite a project. Credit goes to Marian the “CEO of the project.” (Photo taken in April 2010.)

What inspired you to run for ASA president?

I never aspired to be ASA president. There is no campaign for presidency. The nomination committee makes the nominations, looks over the vitas, and decides who is worthy. So you hope they will pick you some time, but you don’t really plan on it.

What was the biggest challenge you have faced in your career? And as ASA president?

My biggest career challenge was the death of my first wife, Clara Lofstrom Green, who died of pancreatic cancer in 1978, after which our family consisted of me, two kids in college, and two finishing high school. It was a great tragedy for us all, but we gained great support from each other. She was a great person and is missed by all of us.

When I was nominated to be ASA president, I immediately went to Elaine Moran and said I was going to be on sabbatical in Oxford, England at All Souls College that coming year. She told me that most of the presidents didn’t actually work at the headquarter office, so my sabbatical wasn’t even a consideration. We could communicate over the phone from wherever I was. This was, however, my biggest challenge as ASA president. My presidency involved lots of transatlantic telephone calls with Elaine Moran (then administrative assistant) and Betty Goodfriend (secretary). This was in the days before email, so business was carried out between three to five English time every Monday afternoon. Betty and Elaine really served as the acting president in my absence and with great skill. They both deserve high praise for their work.

What was your biggest contribution to ASA as president?

I always considered creating a committee for long-term planning to supplement the executive committee meeting that occurred twice a year. Bob Apfel (who was also on the executive committee) and I both thought that it would relieve the burden of the executive committee who often only had time to deal with the very short term problems that arouse at the time of a meeting. The long-term planning committee would have a longer time horizon. Apparently that was not as good an idea as Bob and I thought since the committee no longer exits.

What surprised you most about being an ASA president?

I didn’t find anything that happened as president surprised me. You are just taking over an organization. You had been on the Executive Committee, or at least I had, and the president runs the Executive Committee. I was vice chairman of the psychology department at the University of Pennsylvania during my final year there and chairman at Harvard for three years. So I have had experience with administration. I am not very fond of it, I prefer research, and I have avoided administrative duties ever since.

ASA is constantly growing and evolving. What was the Society like when you were a member? How has it improved and changed?

I enjoyed the Society the most when I first joined around 1955, when it was still small. I would go to talks in other technical areas. For example, I was present when Pat Kuhl gave her famous talk about “chinchilla language.” I also remember hearing, either at a physics or an underwater sound session, about the Cooley-Tukey algorithm we all use today to calculate fast Fourier transforms (FFTs). Now the fields are so technical and advanced that such casual visits to other areas are not so instructive. Special lectures of a less technical nature, given to the whole society, are very helpful.

When I was an associate editor (1970-1973), the editor in chief was R. Bruce Lindsay, who was a famous physicist. We thought of Bruce as an old man. He was born in the 1900s and he was probably 65-70 when I was an associate editor. In our meetings he would come in and say, “Some of you are new, so I’ll go around the table and introduce you.” There were 22 of us associate editors. But, he would go around and say a little about what we each did and even if we were doing something new he would mention that without any notes. We were always really impressed with R. Bruce Lindsay. As an interesting aside, Bruce at 20, took his B.A. and M.S. in physics at Brown University before receiving a Ph. D. from MIT in 1924. During the 1922-1923 academic year he was a fellow at the University of Copenhagen working with Niels Bohr and Hans Kramer. Overall, I didn’t have too much contact with Lindsay as I tried to get my articles in on time and stay out of trouble. But– I knew a man who worked with Niels Bohr!

When I ran for president, my opponent was Lois Elliot. The Society missed a very important potential benefit when I won the election and Lois lost. I can’t believe it took nearly two decades to elect the first female president, Pat Kuhl in 1999. And it took nearly another decade after that to fill the treasurer role–arguably a more important role for making a difference in the Society because of its longer term– with a female, Judy Dubno. The Society has been more open-minded about the qualifications for these offices since I was president.

The way the Society has changed since my presidency seems largely financial. Marian and I attended Roy Patterson’s Silver Medal award in 2015 in Jacksonville, Florida and it was much more elaborate compared to anything we had in my day. When I was president we had three or four people receiving awards. They would each get a very brief introduction and that was it. Then we would go to the president’s room, which wasn’t very large, and alcoholic drinks were made available by the president. Actually, Marian was the one who went across the street to get it! The award ceremony we saw in 2015 was much more impressive; it was in a big ballroom and took almost 2 hours. We didn’t go to the president’s party, but I sincerely hope the president’s spouse did not buy the liquor.

What attributes about yourself have helped or hindered you in your career?

I wish I had more training in mathematics. Signal detection theory is all about Gaussian and multivariate distributions, decision rules, and probability theory. My education was sorely lacking in that regard. In my senior year as an undergraduate at UM, Spike managed to get me into a two-year course for advanced math students. So I spent some time with several hot shot freshman mathematicians, learning things like calculus, linear algebra, and differential equations. As a graduate student I was fortunate enough to have an office at EDG that was next to Ted Birdsall’s office. Ted was a great tutor in mathematics and a great adviser throughout my time at UM. But in all, my math training was disjointed. I always wish I had obtained a more gradual, organized, and complete math program.

What person influenced your career path the most and in what way?

Beyond question, it was Lick (J. C. R. Licklider). He and I made contact while I was a first year graduate student at UM (1955). He welcomed me to the ASA, sponsored my third year of graduate training at MIT, and was a constant source of advice and counsel even after he left acoustics to be a major influence in the development of the internet.

Lick was the president of the ASA ten years before I was. He was also very active and did a lot of good psychoacoustics. Lick had very strong ideas about how scientists could use computers in their work. He knew that submitting data cards to a large central computer and receiving a stack of papers in return, several days later, was not the way to go. Lick saw many of his ideas adopted when he went to ARPA (Advanced Research Projects Agency) and encouraged the development of small personal computers with interconnects among them, a system that eventually became today’s internet. He was smart and had great vision.

Without a doubt, I also certainly owe a great deal of gratitude to Tanner and Swets. In my early days, I never had to worry about my research goals. It was simply to develop and expand upon their ideas about signal detection theory. They gave me a wonderful start.

I also really feel that my students and post-docs along the way have had a large influence on me, as well as on my colleagues and friends in the field of acoustics. Their friendship and support has been a major factor in my progress and development. They all deserve credit, but of particular noteworthiness in the acoustics world are Bob Shannon–who earned the Association for Research in Otolaryngology’s Award of Merit Medal, Roy Patterson and Neal Viemiester –who have both earned ASA’s Silver Medal, and Bill Yost— who earned the ASA’s Gold Medal and was another ASA president (2005-2006).

What is one work-hack that you learned or found over your career and would recommend to others?

I have two. One is get your important tasks done before you go to work. As a tutor and supporter of graduate students and post-docs, I was always available once I arrived at the university. I did all my writing and thinking at home in the morning before I left for school. I usually started my day before six AM and worked until nine or ten AM before leaving for the university. I was an early riser, in part, because of my paper routes when I was younger.

The second hack is how to learn about a new topic. Go to the library, find three or four books on the topic. Read a little of each. One of those books will talk to you. Lick claimed it was like impedance matching as the middle ear matches the sound in air to the sound in water.

What are you working on now?

When we retired I simply left everything and went out to the farm property on the St. Johns River. We got a tractor, tamed the land, and developed our property. I didn’t do anything professionally or in academia for 20 years.

Frankly, I think people stay a little longer in academia than they should and it has not had a healthy effect on American education. Many of the professors are actually giving the same lectures that they first gave twenty to thirty years ago. I thought I had worked hard and done the best I could for nearly fifty years. I had serious doubts about my effectiveness for another ten or twenty. I wanted to try something different and the St. Johns River property provided the opportunity. I have gotten a little more involved since Dave Eddins and Jungmee Lee (both former students), Ann Eddins, and Bob Lutfi (both colleagues) are all now at the University of South Florida.

In the spring of 2019, I was diagnosed with metastatic cancer. I had a small tumor in my left lung, the cancer was the non-small cell variety (medical terminology), not the more aggressive cancer that smokers develop. I have undergone chemotherapy as well as radiation therapy. The results of a recent PETscan shows little activity and will allow me to wait until next May for another CTscan to determine the degree to which the tumor is still active. Now, my major project is trying to get better.

Select Publications of Dr. David M. Green:

Green D. M. (2020). A homily on signal detection theory. The Journal of the Acoustical Society of America 148(1), 222-225.

Green, D. M. (1988). Profile Analysis: Auditory Intensity Discrimination. Oxford University Press, New York.

Green, D. M. (1976). An Introduction to Hearing. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Hillsdale, New Jersey. (Reprinted by the Taylor and Francis Group)

Green, D. M. (1960). Auditory Detection of a Noise Signal. The Journal of the Acoustical Society of America 32, 121-131. https://doi.org/10.1121/1.1907862.

Green, D. M., Birdsall, T. G., and Tanner, W. P., Jr. (1957). Signal detection as a function of signal intensity and duration. The Journal of the Acoustical Society of America 29, 523–531. https://doi.org/10.1121/1.1908951.

Green, D. M. and Swets, J. A. (1966). Signal Detection Theory and Psychophysics. John Wiley and Sons, New York. (Reprinted R. E. Krieger, Huntington, NY, 1974; Peninsula Publishing, Los Altos, CA, 1988.)

[1] Dr. Green served as chair of the Psychological and Physiological Acoustics Committee (1968-1971), was an associate editor on the Editorial Board (1970-1973), and served on the Executive Council (1972–1975) of the Acoustical Society of America.